Evidence of that crisis can be found in the Canadian Women’s Movement Archives, housed at the University of Ottawa Library, in the form of press releases, minutes from meetings, and newspaper clippings.

At the core of the conflict was the idea that conscious and subconscious ideas about race, class and gender can create barriers for certain groups, through overlapping systems of discrimination or disadvantage. At a time when women were working hard to unite as “sisters” in their fight against sexism, the women’s movement itself was being called upon to examine how privileged white women might be ignoring, or even practicing, discrimination within their own spheres of relative power.

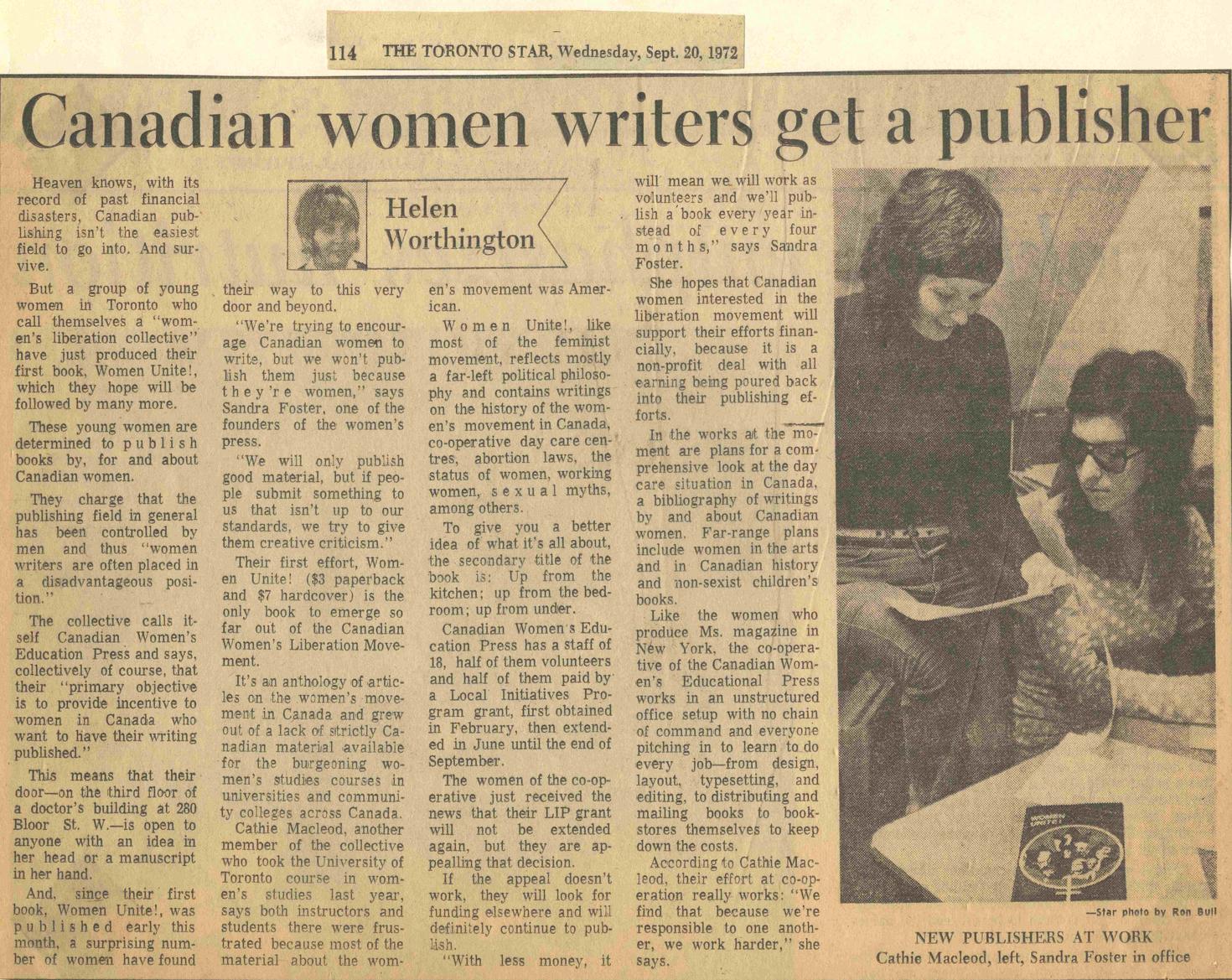

The Women’s Press was one of the first publishing houses in North America owned, operated and staffed entirely by women. The Canadian Women’s Educational Press was founded in 1972 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Toronto Women’s Studies department and several members of the Toronto Women’s Liberation Movement, one of the first feminist political organizations in the country.

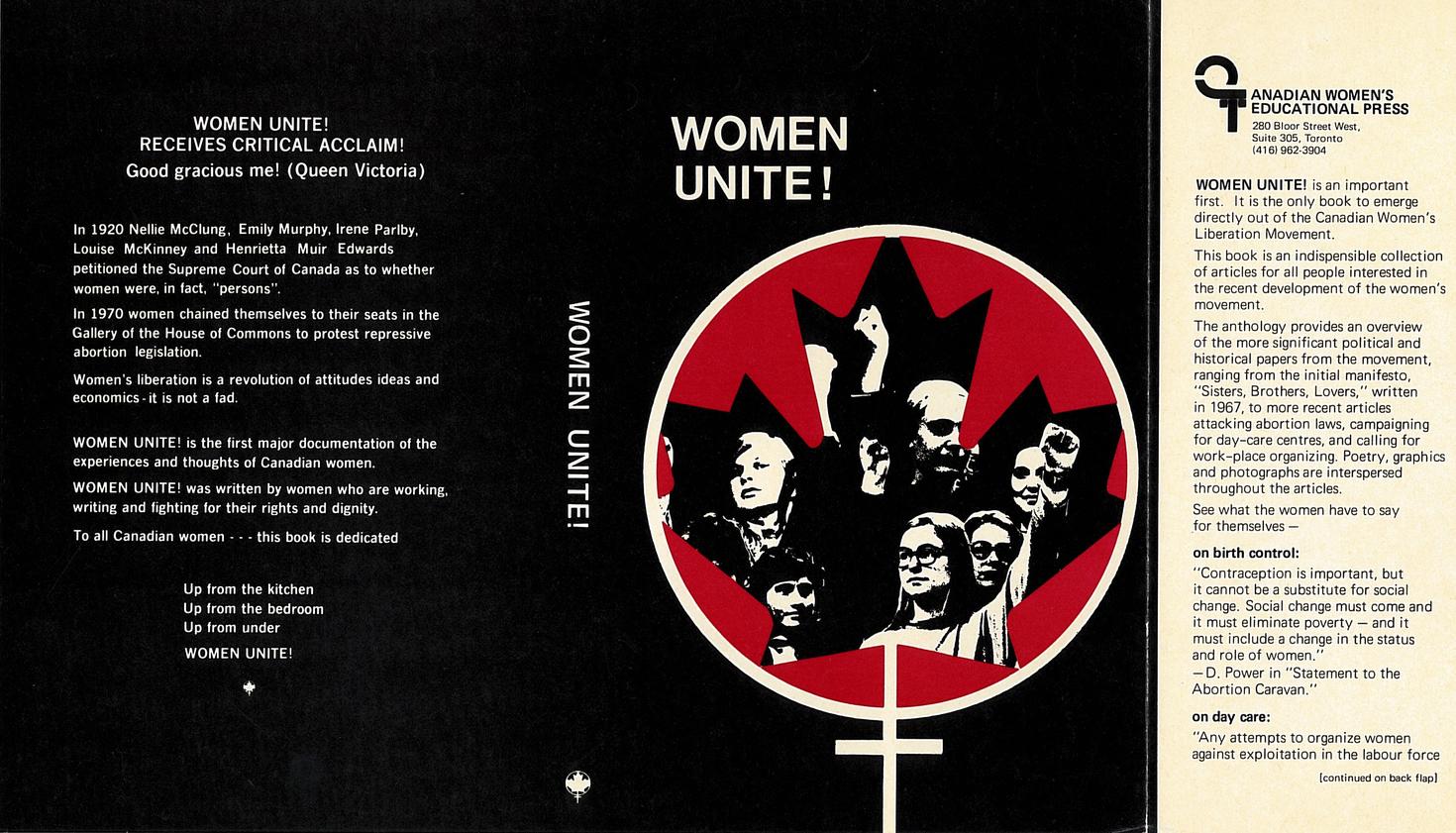

Concerned about the dearth of published materials documenting the women’s movement in Canada, the group had put together a compilation of Canadian feminist writing in 1971 called Women Unite: Up From the Kitchen, Up from the Bedroom, Up from Under.

Even though Canadian publishing companies employed a greater proportion of women than most other industries at the time, few female employees were in positions of power in publishing houses. Women were certainly not making decisions about what got published, and books written by women were too often overlooked. When Women Unite was rejected by several mainstream publishers, the group decided to establish a publishing house run by women dedicated to publishing writing by women.

With the help of a grant from the federal government, The Canadian Women’s Educational Press – later shortened to The Women’s Press and known colloquially as The Press – was incorporated on March 22, 1972. The Press’s stated goals were to make space for female voices in academic publishing and to make feminist ideas more accessible. The structure of the operation would be non-hierarchical, and its processes influenced by consciousness-raising collectives, key drivers of the second wave women’s movement at the time. These collectives operated by consensus decision-making, and The Press followed suit.

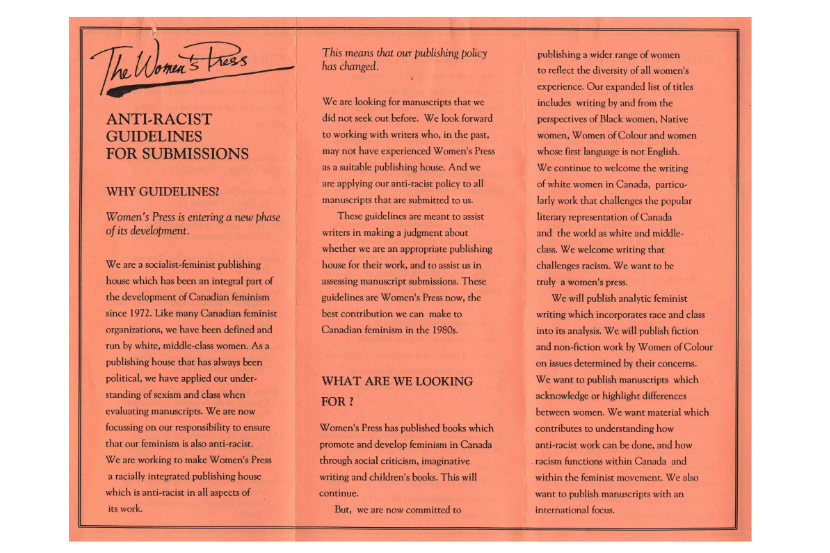

The collective aspired to be anti-sexist, anti-capitalist and anti-racist in its approach, but by the mid-1980s some members were concerned that results were falling far short of these aspirations. The organization was run by white, middle-class women and the Press’s publishing lists contained almost no books by women of colour.

It was in this context that Ann Decter got involved in the Press, just as discussions on the need for an anti-racist policy were getting underway. Decter was among a group of younger women who became part of the push for change, although she notes that some of the more established editors, such as Maureen FitzGerald, were also part of this push.

At the time, The Women’s Press “didn’t look any different from the mainstream publishers on that issue (representation), and we thought we should,” says Decter, who was 29 in late 1985 when she joined The Press as a volunteer.

The Press was run by about two dozen unpaid members, as well as five paid staff members. There were several working groups made up of volunteers. The governing body was the Publishing and Policy Group (PPG), made up of 16 women who were responsible for approving manuscripts for publication. The PPG had been a rather homogenous and closed group, Decter said, but this was changing, thanks to a growing awareness of the need for more diversity.

The group agreed on a restructuring that brought new voices into the mix, Decter explains. Members of the volunteer working groups were invited to be a part of the decision-making body. This process brought some women of colour and their allies, into the decision-making group.

“That’s I think what made it possible to push for change,” she said. “The people involved began to shift a bit and some people were conscious of the need for more diversity and were working for it. They were conscious of the fact that through the way it had been organized and existed, it wasn’t very representative. (Members of the PPG) would invite people they knew in and they moved in their own circles. So, it was this informal stuff that caused The Press to be the way it was.”

But these changes did not come without friction. In June of 1987, work began on a collection of creative fiction called Imagining Women. Press members sent out calls for submissions and a manuscript subgroup of the PPG accepted 21 stories for publication. Contracts were signed with the authors and the editing process got underway.

But several months later, the wider PPG, which now had several women of colour as members as well as others who were concerned about lack of representation, voted to exclude three of the stories from the collection. They charged that the stories were written by white authors who had appropriated the voice and style of people of colour while reflecting upon Latin American and African experiences the authors had not lived.

Conflict ensued as Press members discussed the project, with some arguing it was unprofessional to cancel contracts that had been signed.

“In the moment, it came down to addressing what was more important, taking a stand as an anti-racist publisher or following the norms of publishing in which you wouldn’t cancel a contract on someone. That’s where the conversation around cultural appropriation opened. And that to me was one of the big points of articulation of difference at the Press.”

Lines were drawn between long-standing members of the collective, who backed the three stories, and the majority of members, who wanted to see The Press adopt a more radical approach to anti-racism. At the same time, tension arose around a proposed all-women-of-colour anthology and there were heated debates about the anti-racist policy itself, which had not yet been formally adopted.

On May 11, 1988, a group of ten Press members, calling themselves the “Popular Front-of-the-Bus Caucus” issued a two-page press release on The Women’s Press letterhead, declaring that The Press was “just one of many organizations in the women’s movement which has found it necessary to examine its own racism and its contribution to racism within the women’s movement.”

“The Women’s Press (is) really a white women’s press. We are working to break out of the ethnocentric isolation.” In describing how that process had broken down, the press release further mentions a “general denial of the internalization of racism at the Press” by some members, and a “lack of confidence in working with a group of women of colour.”

“We feel that our continuing engagement with women who resist the implementation of anti-racism at the Press is now working to the detriment of the Press and the women’s movement,” it concluded. “As positions are now polarized and entrenched, it is necessary for us, as a majority caucus, to take a leadership role by making our position public.”

Five days later, another press release, also on The Women’s Press letterhead but signed by a different group of women, was circulated.

“For more than a year, the Publishing and Policy Group and other members of the Press have been involved in debate over what explicit forms a more conscious anti-racist policy should take,” says that release.

It goes on to say there was no debate among Press members over the fact that racism is a “deeply systemic problem woven into the fabric of our society and our lives.” Nor was there debate over whether a new policy should be adopted, it said, but rather how this should happen.

“An atmosphere quickly developed in which it became very difficult to propose concerns and differing opinions without incurring severe personal attacks…In recent months we have seen writers for the Women’s Press treated with open disrespect and heard the books we’ve published over the years dismissed as being of little value because they are not sufficiently anti-racist.”

At the height of the controversy, a long-time staff person, Margie Wolfe, was suspended and then fired, and the locks on the doors to the College St. office were changed.

Four of the members who signed the second press release, including Wolfe, ended up forming a new press – the Second Story Press. One of their first publications was a collection of stories, called Frictions, which included the three stories that had been removed from Imagining Women.

The remaining women at the Press went on to publish a set of guidelines for anti-racist publishing, which read in part, “We will avoid publishing manuscripts which contain imagery that perpetuates the hierarchy black = bad, white = good. We will avoid publishing manuscripts which adopt stereotypes . . . (or) in which the protagonist's experience in the world, by virtue of race or ethnicity, is substantially removed from that of the writer . . . (as well as) manuscripts in which a writer appropriates the form and substance of a culture which is oppressed by her own.”

The Globe and Mail reported on the controversy on Aug. 9, 1988, quoting Popular-Front-of-the-Bus caucus member Katherine Scott: “The best writing comes from your immediate experience. You cannot speak for someone else. Whites have done that for years. It’s a real legacy of colonialism.”

The same article quotes Wolfe, the staff member who was fired and went on to help launch Second Story Press: “The approach of the caucus to writing is that they feel they have a right to tell a writer what to write about and what not to write about. Does that mean that if I come from a certain background, from a certain age, that I have no right to try to explore other cultures, other experiences? If you take that to its logical conclusion, where does that place the imagination and where does that place creativity?”

Decter says the media at the time seemed to dismiss those who rejected cultural appropriation as censors. But it is not censorship for a publisher to be selective about which books it will publish, she argues.

“We had a small list,” of books that could be published each year. “And if we were going to publish a book by a white woman about an indigenous woman’s story, we weren’t going to publish the book by the indigenous woman about her story.”

She and other white women at The Press came to the realization that “maybe that’s why (we) were not publishing First Nation writers, for example, because you filled that space with someone else’s voice.”

Decter said that those who stayed at The Women’s Press worked hard in ensuing years to make their publishing list and their members reflect the diversity of the wider community. They examined their structures and procedures to identify and remove barriers, and gave more women of colour decision-making opportunities. Decter eventually became a co-managing editor of the Press along with Angela Robertson, a Jamaican-Canadian woman involved in the Black Women’s Collective.

While the media coverage of the controversy focused on what The Press had decided not to publish, the thrust of the new anti-racist approach was about what The Press would make room to publish instead, Decter explains.

“We weren’t focused on a discussion about what white people get to write, put it that way. We were coming from the point of view of a publishing house with political values and goals and saying, ‘What kind of feminists are we if we are basically only publishing white writers or almost all white writers?’”

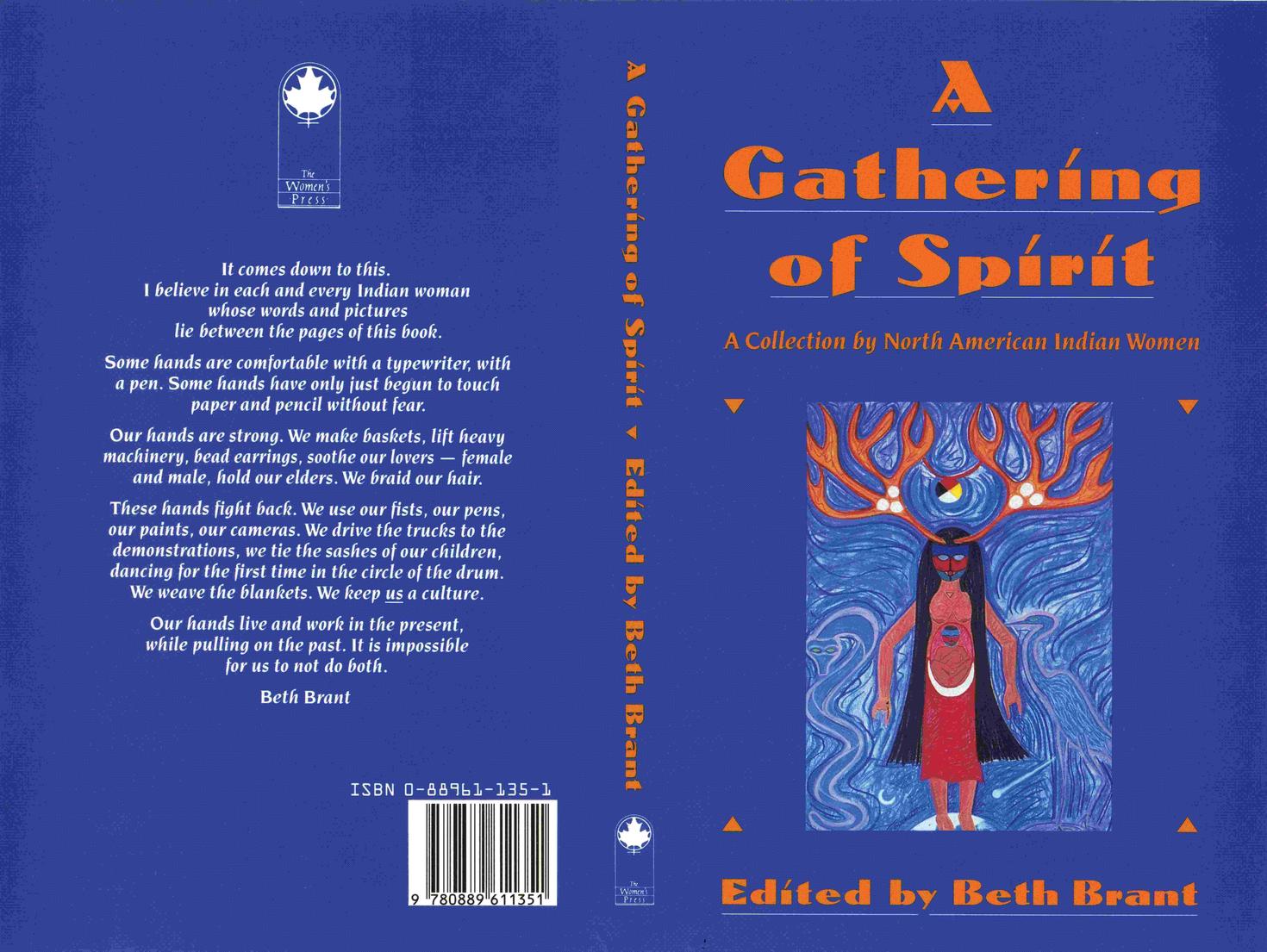

In the years following the split, The Press went on to publish many books by women of colour, including: Asha’s Mums by Michele Paulse and Rosamund Elwin, a children’s book about a black child and his Lesbian mothers, Parastoo, a collection of stories and poems by Iranian-born Mehri Yalfani, and essay collections by Mohawk writer Beth Brant and Indo-Canadian scholar Himani Bannerji.

The split at The Press was difficult personally, Decter said, as women who had worked together for years and shared a passion for books and feminism found themselves on different sides of the issues.

“So those things were really difficult but in terms of what needed to be done, in terms of the learning, the growing, the becoming a better person and finding a better way to be in the world, it was amazing. I still rely on things I learned then from time to time.”

Decter, who is now a senior director at the Canadian Women’s Foundation, a feminist philanthropic organization, notes that debate about cultural appropriation has continued in the decades since the split at the Women’s Press, and many have changed their views on the subject.