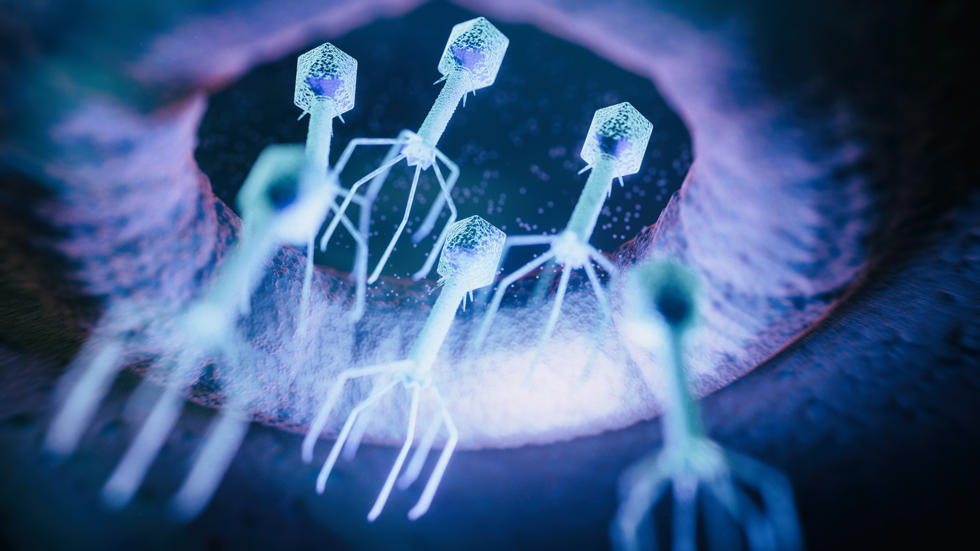

Their viral quarry wasn’t hard to find. Bacteriophages, or “bacteria eaters,” are the most abundant biological organism on Earth. They’re everywhere bacteria are found – ubiquitous in dirt, water, the human gut microbiome. Locked in a coevolutionary battle with their germ hosts since the dawn of time, scientists believe there are more than — wait for it —1031. That’s more than 10 million trillion trillion.

To put that mind-bending figure in some kind of perspective: There are vastly more bacteriophages – just phages for short – than grains of sand across the globe. There are believed to be 10 million times more phages than stars in the visible universe. They’re busy, too. Each day, half of all ocean bacteria are infected and blown apart by these replicating microscopic assassins in a forever war.

Unveiling a hidden world to undergrads

Introducing the fascinating world of phages to students and teaching them how to find ones that are completely new to science is a passion of Dr. Adam Rudner, associate professor in the Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology, and Immunology. His work in discovery-based laboratory courses has recently earned him a uOttawa Excellence in Education Prize.

Dr. Rudner’s vision made uOttawa the first Canadian university to join the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s (HHMI) program focused on phages and aimed at exposing undergrads to research methods, experimental design, and data interpretation. It plugged uOttawa into a broad network of institutions supported by the Phage Hunters Advancing Genomic and Evolutionary Science (SEA-PHAGES) program.

The first “Phage Hunters” class at the Faculty of Medicine was held in 2019 with 16 students. It’s now a required lab course, taught in five sections, for 80 third-year TMM students. The students complete class benchmarks: Purifying and amplifying their found phage, isolating its genome, doing “restriction fragment length polymorphism” (RFLP) analysis, among other things.

“While they learn fundamental microbiological techniques, I think the larger research experience is much more important for their development as independent researchers,” Dr. Rudner says.

It has led to a much bigger teaching load and a complete shift in Dr. Rudner’s laboratory’s research focus. He says the Faculty has been “incredibly supportive” as this transition has ramped up.

“A mid-career change is unusual, and it has been exciting and challenging,” he says.

Exposing students to the rewards and trials of research

One of Dr. Rudner’s goals with uOttawa’s SEA-PHAGES program is introducing undergrads to the satisfactions and potential triumphs of lab research, but also steeling them for the challenges of drudgery and experimental failure.

“Confronting failure obviously can teach students about improving experimental technique, controls, and what types of experiments yield interpretable results. Drudgery is a drag, but if you are committing to graduate work – many of our students pursue MSc or PhDs – it is important to make sure you can handle this. It can also force students to think about ways to innovate techniques,” he says.

For instance, each student does 50-100 plaque assays a term. There are multiple opportunities to learn via failure during this plating process. Challenges can quickly arise because some phages prove harder to work with than others. But this might be a sign that a student has unearthed a new-to-science phage specific to the bacterial host.

“A challenging phage is more likely to be unique,” says Dr. Rudner, who earned his PhD at the University of California, San Francisco, and did his post-doctoral research at Harvard University.

The students earn naming rights. After all their hard work finding and isolating a new bacteria-specific phage, the students get to christen their finding with a name and enter it into an international database.

Pivotal lens for many students

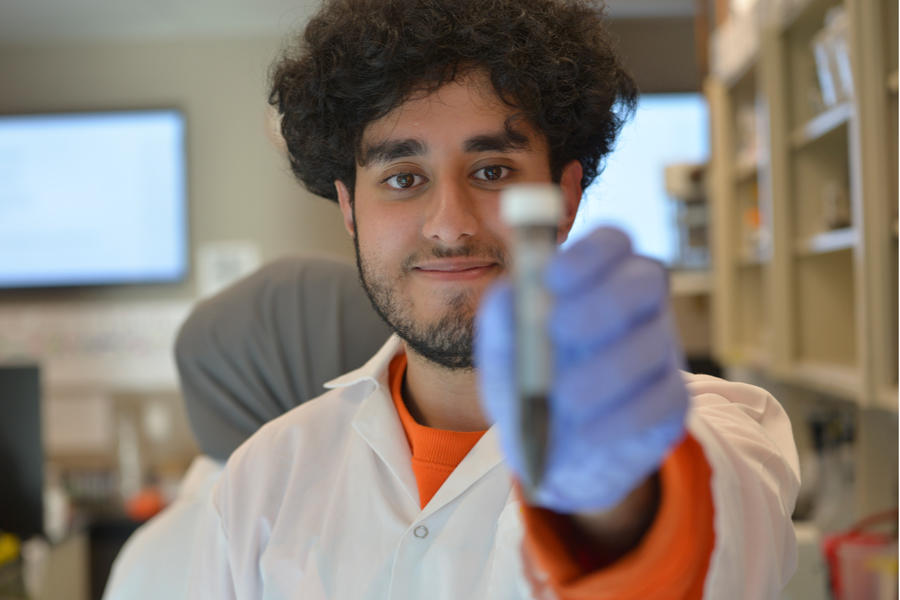

Zachary Mitchell, in his fifth year of the TMM BSc-MSc program and now guiding students in the ways of bacteriophages as a teaching assistant, says his experience in Dr. Rudner’s phage discovery lab affirmed he’d pursue research at the graduate level. The native of North Bay, Ontario, aims to one day work as a phage lab technician in academia or biotech.

“As I have spent more time studying them and learning how rapidly they evolve and how biologically diverse they are, I've come to realize how relatively little we know about the fundamental biology of these viruses. Now, trying to answer questions about the biology of recently student-discovered phages is my principal interest,” Mitchell says

Along the way, he's discovered two phages, naming one “EnochSoames” after a character in a story by English essayist Max Beerbohm, and the other “SunWukong” after the Chinese religious figure from Wu Cheng'en’s novel Journey to the West.

Emily Wood, a 4th year TMM BSc-MSc student in Dr. Rudner’s lab who aims to eventually work in oncology, says her experience isolating her phage from a tube of backyard soil and then fully sequencing the genome made her feel “so much more ownership over my work in the lab.”

“The course design allowed me to experience and practice a variety of lab techniques and experiments that I feel prepared me for future work in any biomedical research lab. And the lab environment allowed room for trial-and-error and fun along the way,” says Wood, who grew up in Caledon, Ontario.

She dubbed her novel phage “Superstar,” inspired by a Taylor Swift song and what she felt was the virus’s big-league charisma. Now, for her master’s project, she’s isolating and characterizing bacteriophages that infect Staphylococcus epidermidis, a bacterium that often colonizes implanted medical devices and can be highly antibiotic resistant.

A growing field with buzz

Discovered by accident more than a century ago by two scientists who were investigating why their bacterial lab cultures were getting obliterated, phages have shown unique capacity for treating bacterial infections. They may also be a finely-tuned weapon against “superbugs” and antibiotic resistance, an escalating scourge that the World Health Organization has defined as one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development.

Presently, phage therapy – used for decades in eastern Europe to treat bacterial infections – is experimental in Canada and it is not available outside of clinical trials. But things may be changing on that front in North America. There are various active trials and some prominent U.S. universities have started phage therapy institutes.

“There is lots of promise and buzz around phage therapy, and it is slowly becoming something being funded and supported around the globe,” Dr. Rudner says. “There is also lots of promise for using phages in agricultural settings – where the majority of antibiotics are used/misused – and in areas such as food packaging, band-aids, topical use in acne creams, oral use to prevent plaque.”

Dr. Rudner says the thriving program at the uOttawa Faculty of Medicine will evolve along with the science and the lab’s discoveries.

“My lab is pursuing a few projects that have leveraged the undergraduate research and are now turning into cool stories and may provide phages for phage therapy trials at The Ottawa Hospital,” he says.

Support the Faculty of Medicine today! Use the designation field on our online donation form to support the 'Student Assistance' fund.